|

Cell Culture, also known as tissue culture or TC, is where the majority of experiments start. A lot of cancer research depends on what we call “models”. The drugs, therapies, interventions etc. we test can be very harmful to humans. It’s also very difficult to watch cancer progression in someone already suffering. You use models such as “cell models” and “animal models” to mimic the human body. It’s not always perfect, but it’s better than giving a highly toxic drug to someone on a hunch it might work. The first stage of model testing is "cell modelling". If the results are promising, you move on to "animal models" or if there is good indication of the safety it may move straight to humans.

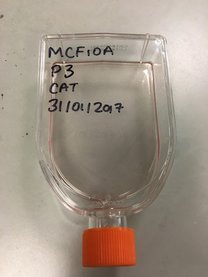

What are “Cell Models”? Cell models are cells from tumours which are grown indefinitely outside of the body and are experimented on. “Cell line” is the name given to these cells. Cell lines come from actual people. The most famous is the HeLa cell line, which came from an African-America woman, Henrietta Lacks, with cervical cancer in the 1950’s and 1960’s (for more information you can read the book “The Immortal Lives of Henrietta Lacks” by Rebecca Skloot, which is very good - not sponsored just enjoyed the book). Cancer has a very unique characteristic which makes it hell to get rid of. Cancer cells are immortal. Like a vampire (though not as sensitive to sunlight) cancer cells cannot die. They will continue to grow and multiply as long as there is a steady blood supply (very like vampires so). Why blood? Blood carries food and oxygen all around your body and removes all the bad stuff from your organs such as toxins and carbon dioxide. But back to cell lines. When a tumour is taken from the body you can isolate individual cells. You grow them and if they keep growing they’re known as a cell line. The vast majority of cells from tumours from a person cannot make a cell line. It’s like a lottery to which will survive. Cell lines are named after the person they come from (like Henrietta Lacks) or from the institution they were isolated in. The most common breast cancer cell line is MCF7. MCF stands for the institute where it was “made” – The Michigan Cancer Foundation. 7 stands for the 7th attempt (the successful attempt) to “make” the cell line. The cells were from the mammary tumour of 69-yr old Frances Mallon, a nun in the convent of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Michigan. This cell line is a model for oestrogen receptor (ER) positive breast cancer. ER+ is one of the most common mutations in certain breast cancers.

What are 2D and 3D “Cell Models”?

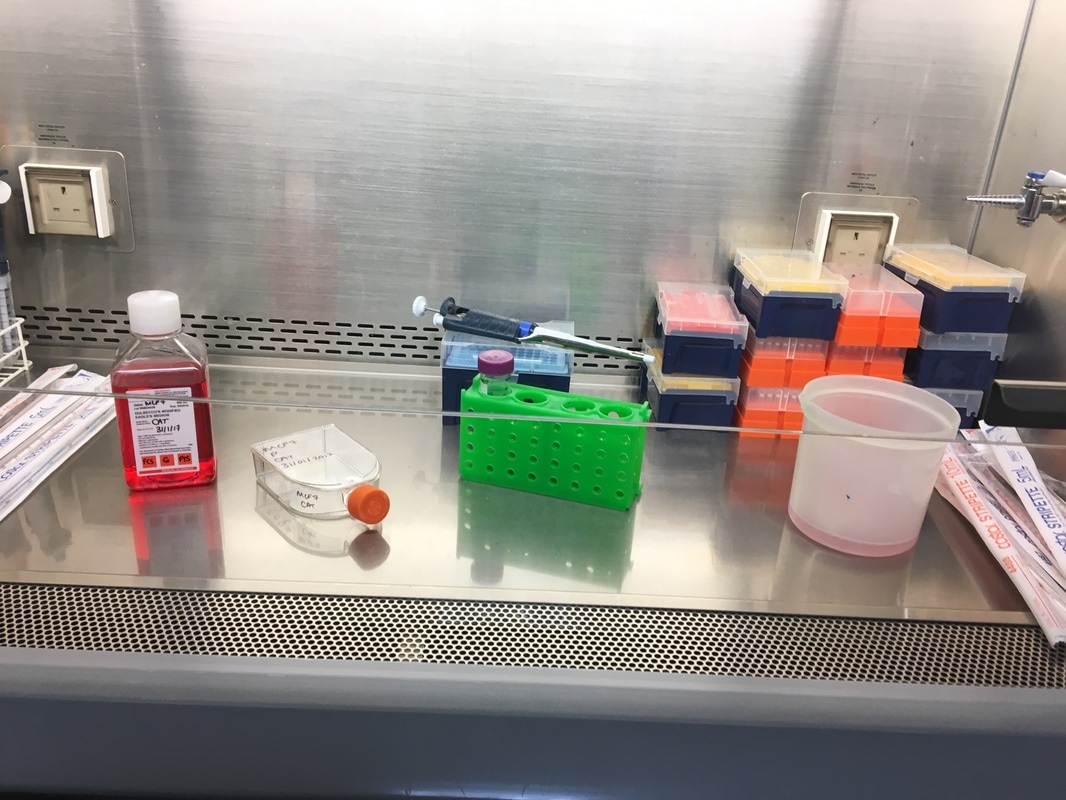

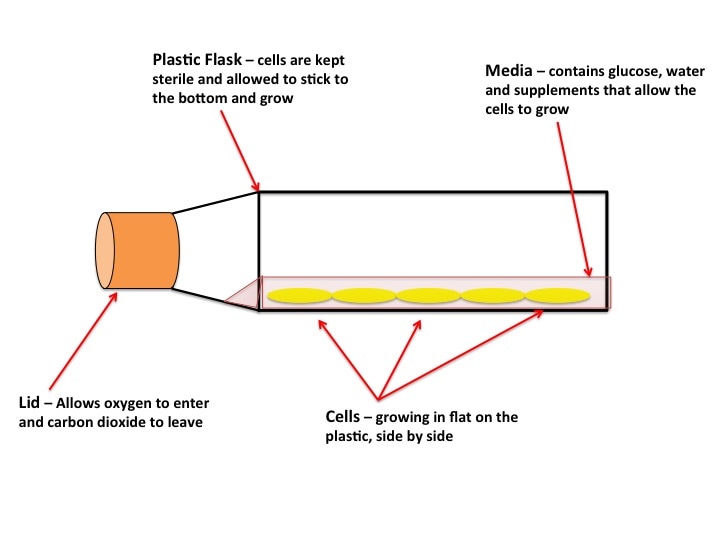

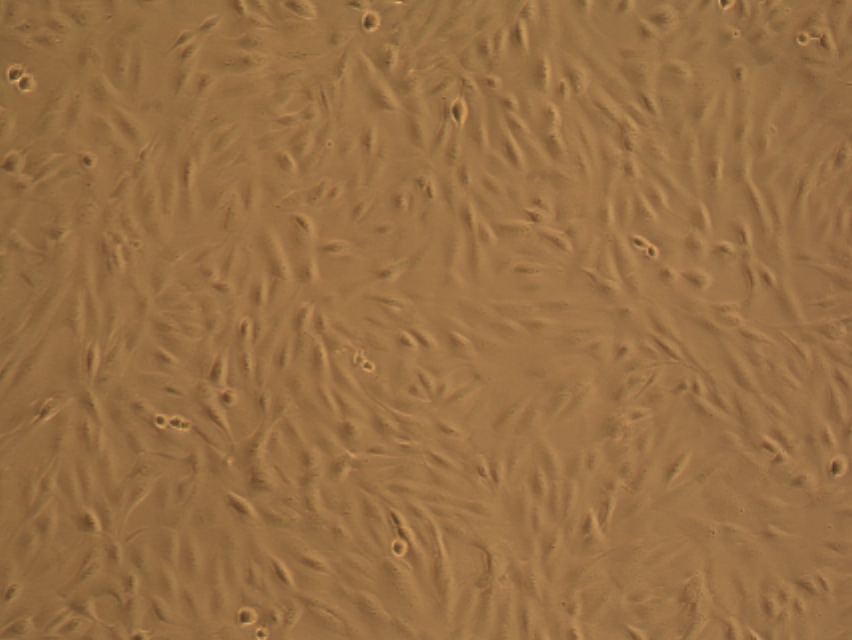

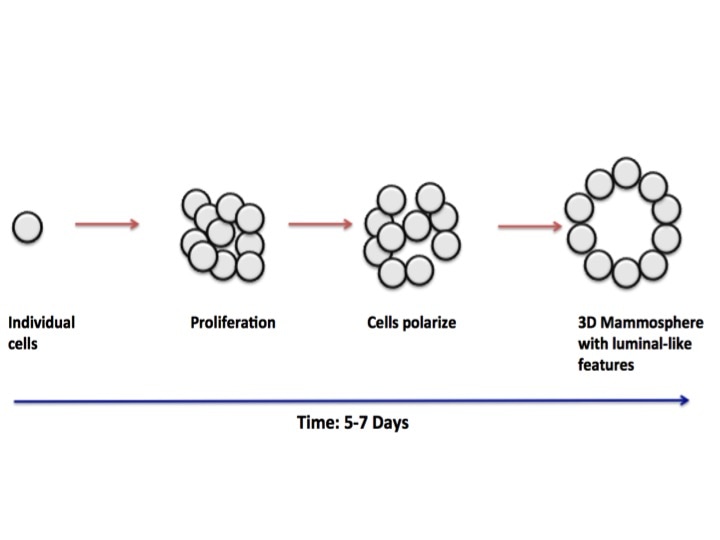

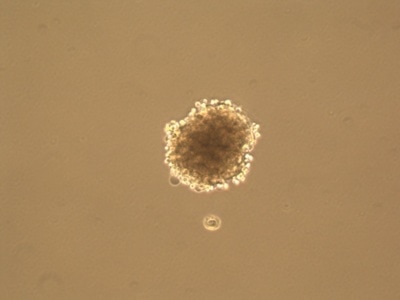

As you can see in the pictures, cells typically grow in 2 dimensions, i.e. they sit flat on the plastic and grow side by side. But you are not flat! You are in 3 dimensions. 2D culture is very easy, it’s cheap and it’s (relatively) fast. But if cancer has taught us anything it’s that they constantly mutate. When cells grow constantly in 2D they start to lose the ability to do certain things they would normally do in your body, for example the way they attach to each other. This is where 3 dimensional culture comes in. 3D culture allows the cells to attach to each other, typically in a ball or sphere (see pictures). These “spheroids” more closely resemble the body, giving researchers a better idea of what’s happening. The only problem is 3D culture takes A LOT of time, skill and patience. It is in fact very difficult and is not done in standard experiments yet.

Final words

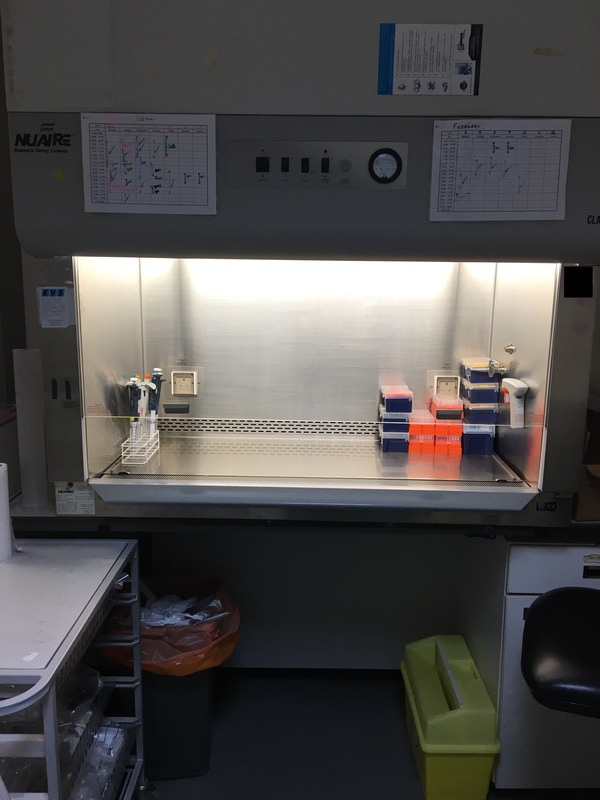

One final thing about cell culture, which anyone who has ever done it will attest to. Cell culture is back breaking. Because these cells are so important but also because they themselves can contaminate other cells very easily, you entire work is kept sterile. You are in a hood (see pictures) with a constant stream of filtered air. You can’t put lids etc. down so your arms are constantly in the air (not really able to rest on the hood) and you can only open the window a small amount, meaning a lot of awkward stretching. You could be in cell culture for hours and hours slogging through 3 to 4 different cell lines and making up lots of different experiments. And usually this is almost every day. But you cannot leave it, even for a day. These annoying little cells are the fulcrum around which your experiments are based. It’s odd to think about wanting to keep such deadly cells “healthy” and “happy” when all you want to do in the body is destroy them. But to destroy something like cancer you have to understand it, so I’ll keep the little feckers happy if it means keeping a human healthy.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Caitriona and I am a PhD student at Imperial College London, UK. Categories

All

|