|

Just as a quick update!

As of 2.41pm Thursday 21st February I am writing my thesis! It's going. Writes itself really...

1 Comment

I wanted to do a quick post about what it means to be a PhD, what you have to do and how you become a doctor. Not a useful doctor mind but heck you've earned that Dr. in front of your name you tell the world!

I know I should have done this in the beginning but hindsight people! What is a PhD? You can get a PhD (or Doctorate in Philosophy for those nerds out there) in pretty much anything. If you have the will, the money and a supervisor you get that PhD in the history of snakes in Ireland. The majority of PhDs you'll hear about however will be in science subjects. Maybe some arts subjects (literature etc.) but the effort required to get a doctorate vs the usefulness to your future career means it's typically science-y types doing them. I am very happy to be told about any PhD's readers have done in any subject. How Long is a PhD? A PhD usually takes between 3-4 years however that changes wildly from country to country. For example in Scandinavian countries you are required to publish in a peer reviewed journals to be eligible to sit your viva (more on that later). In the UK and Ireland you are not required to publish. In the USA and Canada PhDs can take 5+ years and again some Universities will require you to publish before you get your doctorate. Again I don't know the rules for every country. My PhD is from Imperial College London and they have a max 4 year policy (unless there is some MAJOR need to delay your studies e.g. pregnancy). I am not required to publish. So my PhD is 4 years. Who pays you? There are a few ways of paying for your PhD. The usual way is by external funding. This can be from a charity or research council. Applying for funding requires a lot of jumping through hoops and a solid research proposal. The funding process is HIGHLY competitive and a lot of great ideas get left to the wayside. But there's a finite amount of money available and funding bodies need some sort of guarantee that the information generated will be useful for the future. If you feel this is unfair donate to your charity of choice if you know they fund PhDs. This is not an ad but CRUK runs a PhD sponsorship scheme. Another way of doing a PhD is self-funded! Oh yeah. You find the funding yourself or you pay yourself through. I have also heard of supervisors getting funding and they hire PhD students and pay them. It's slightly different from external funding because in external funding, it's awarded to the PhD not the supervisor. Your funding also decides how long your PhD will take. If you have 3.5 years funding you realistically should be finished in that time. What is the funding used for? There are three areas your funding goes into:

What does a PhD student do? I have to say this (and it always gets me) while we may be considered students we ARE NOT students. It's like a job except not 9-5 and definitely not paid well enough. I never had to go to lectures and I never did exams. I could choose to attend lectures (for example I went to some MSc in Epidemiology lectures to learn about a subject I didn't know about). My department also ran seminar series and guest lectures for the whole department but again not mandatory. What I did was work 70+ hours a week in the lab and doing bioinformatics until I got some results I could write into a cohesive story. However I will note I except we are students when it comes to student discounts! You gotta use what you can! How do you get your "PhD"? You need to complete a set period of work (3-4 years) which you write into a thesis (in Imperial you do a max of 100,000 words). You then submit this thesis for evaluation and do a viva. A viva is a defence of your work. In my case, I will submit my written thesis to two examiners (an internal and external examiner) who are familiar in my field. They read the thesis and then we come together to discuss the results. I am asked questions and I have to defend my choices. It can take between 2-5 hours to do a viva defence. In other countries your defence is in front of a panel and is open to the public. So you could be standing up in a room full of people (grannys, children, your neighbour) and have to defend your thesis. Usually this happens in countries where you are required to publish. You are already peer reviewed so the defence is more general. One you complete your defence you are given corrections. These can be minor, for example asked to fix typos or a section of your written work, or (god forbid) major corrections, which usually require you to return to your lab/office/hell to re-do work or do more work. How do I get a PhD? The best advice I can give you is be open. There are a few ways to go about getting a PhD. (1) You can pick subject(s) you want to study (I chose epigenetics and cancer) and research all the main people in this field. Contact these people and explain that you would love to do a PhD with them and would they have the ability to come up with a research hypothesis and apply for funding. (2) Doing an internship/research assistant role in a lab you want to do a PhD in. You will have the ability to show your skills and know when the PI (principle investigator) is applying for funding etc. (3) Go on www.findaphd.com/ NO JOKE! This is how I did it, I went on Find a PhD and searched my keywords. I found a PhD I liked the look of, got an interview and hey presto I got a PhD. Most labs will try to fill the position internally first (see point 2) but if they can't find a suitable candidate they will advertise publicly. Is a PhD hard? Yes. Next question. I joke. A PhD is hard as hell. It's meant to be. But it's also meant to be rewarding and you learn a lot, not just about your subject but about working in that environment and with other people. What else do I get from a PhD besides a doctorate? That is completely up to you. You make your PhD what you want. Some people will just do their own work and finish. I however did not do that and I encourage anyone thinking of doing a PhD or doing one to use your time. Teach, whether you do GTA work with undergraduate students or mentoring masters students. Teaching will give you so much in return (not just extra cash - always useful) but also new ways to communicating with others, new ideas and most importantly HELP! I have had three masters students throughout my PhD and if I didn't I wouldn't have the results I have. If you give time and experience to them, they will reward you. Trust me. I also did A LOT of research engagement, probably the most out of any of my peers. I literally said yes to every opportunity that came my way. Why? Because chatting to people about science is AWESOME! I mean come on I'm doing a science blog. It is just so rewarding. I also advise doing courses if you can, I participated in a MSc in epidemiology and did a number of Professional Skills Development Courses (like how to write a literature review, how to make a poster etc.) which really helped my writing and communication skills. As a PhD you are a part of a University or Institution. Use those connections to make the most out of your PhD. Should I do a PhD? Honestly I don't know. That is for your to answer. From my experience, if I had been honest with myself I would've probably not done a PhD. I was not and still am not mentally sound (in my opinion) to do a PhD. You require strength and determination. You will be knocked down a lot but getting back up and ploughing on will stand to you. Having said this I don't think anyone would've gotten the results I did or adapt their work the way I did. What you produce is unique and that's worth it. If you want to do a PhD and you really like your subject, do a PhD. Also we need more scientists in the world so if you're a science student wondering if you need to do a PhD PLEASE DO ONE! WE NEED YOU! Did that sound desperate? What does your PhD mean to you? I am not sure how to answer that question really. Stupid since I'm the one who asked it. I have a had a lot of struggles throughout my PhD. Struggles which as sadly not unique. I went back on anti-depressants, I had to deal with an eating disorder and I may or may not have tried on numerous occasions to hurt/kill myself. It sounds dramatic but mental health issues in PhDs are not uncommon. You are under a huge amount of stress and have to cope with doing things mostly on your own. This information shouldn't deter you from doing a PhD. I had mental health issues before I started. I may have struggled and I did have to stop my lab work early because I couldn't cope but I also would go back and do it again. I would do it better (obviously) but I would do it again. Doing a PhD has shown me (1) how smart I actually am, (2) what I am passionate about and (3) how strong I am. Plus who doesn't want to say "I'm a doctor" when asked on a plane if there is a doctor on board. Fair enough you do have to add that you in no way are you a medical doctor but god dammit you earned the right to say it! So that's it! Again if you have any questions please don't hesitate to contact me.

Recently the European Association for Cancer Research (EACR), who as you know funded me to travel to IARC in Lyon to work, launched a blog competition. The idea of the competition was to write a short blog-style post about "Life in the Lab". You were allowed to submit as many blogs as you liked so I submitted three:

I found out today that the first one (Engaging with the (scary) public – why we need to do it and do it now) was shortlisted as one of the best blogs submitted. So while I didn't win, it will still get published in the next few months. BUT what I also learnt was that they liked my other two so much that they are going to published anyway probably early next year! How awesome is that! Since they are going to be published I won't be adding them up here but watch this space. Once they become available on the EACR magazine website I will let you all know!

Yesterday I was at the New Scientist Live exhibition in the ExCEL London with CRUK (sorry I am terrible at taking photos so eh no evidence). My job there was to chat to the future scientists from 13 year olds to 23 year olds about how to get a career in research and what it was like to do a PhD. And my one biggest piece of advice was do coding! Bioinformatics is the future. Seriously, even if you hate maths (like me) learning some code language will help you in anything you do.

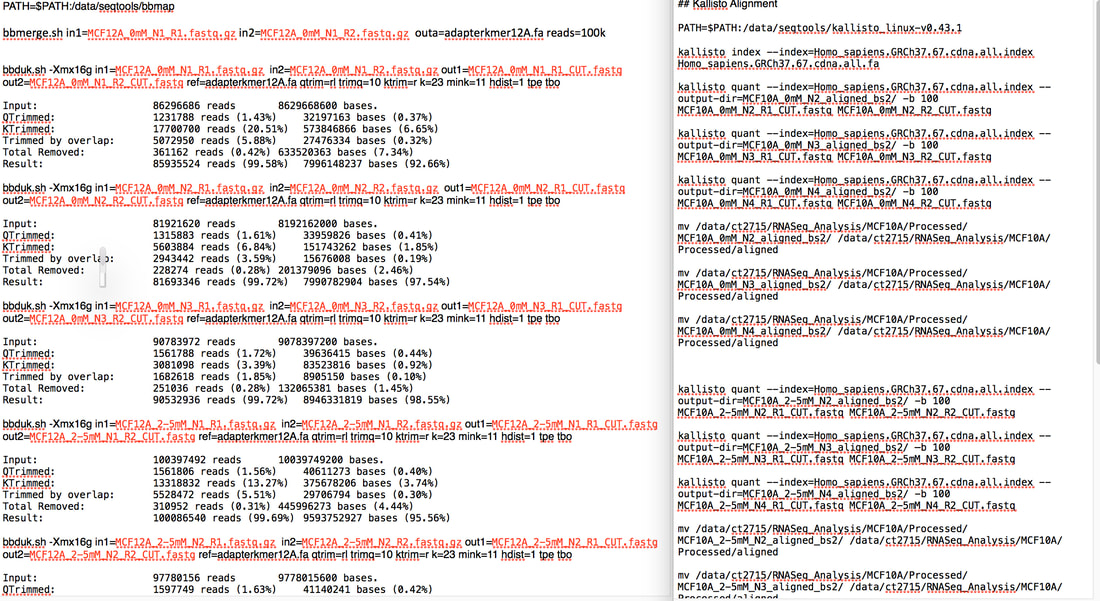

My other piece of advice was that if you want a PhD google www.findaphd.com/ because it does exactly what it says on the tin. It found me a PhD. So what is bioinformatics and why is it important? Bioinformatics is basically the analysis of biological data. Biological data usually means sequencing data. You use a coding language such as R, python or unix to analyse this data. The above picture is my code for doing quality control on my RNA sequencing data using unix. I can also (barely) use R. To me python is a snake... Bioinformatics is important because we can take massive amounts of data from hundreds or thousands of different samples and use this to generate more knowledge about areas such as cancer. This can be sequencing the entire compliment of genes in tumours of hundreds of patients to see if there are common mutations. This can tell us what these tumours have in common and what they don't. You can use this information for example to find "driver mutations" which are mutations commonly found in early stage tumours (p53 mutation is a driver mutation as some cancers require loss of p53 to develop into cancer). The idea of using whole genome sequencing in cancer has come up a lot recently in the news. And the people who are taking this data and finding interesting results are bioinformaticians. Pretty much every cancer research lab in the world is generating data which needs to be analysed computationally. The data you get collectively from sequencing etc. is called "Big Data". However while most labs are generating this data, a large amount of those labs have no one to analyse it. We need more bioinformaticians to take this data and make it useful. Hence why bioinformatics is the future. The dawn of the era of joint experimental and computational scientists is dawning. I am an experimental scientist (i.e I could barely use excel let alone do big data analysis when I started my PhD). But I had to learn how to use R and unix to analyse my data because frankly there was no one else. And this learning was something actively encouraged by my supervisor. Every PhD and post doc James has now can do both. It's very important to him. It really should be more important to a lot more supervisors. So here's my experience: I have done two types of sequencing experiments generating data on DNA methylation (Illumina MethylationEPIC Array) AND gene expression data (RNA-Seq) of two non-cancerous cells treated with metformin. What this gives me in a massive amount of raw data (like hundreds and hundreds of gigabytes - the total amount of data generated from my RNA-Seq was roughly 2-3 terabytes...yeah). I took this raw data and ran it through quality control to make sure every piece of information I got is the best quality. I then ran analyses to determine if there are differences between DNA methylation levels or gene expression levels between your untreated and treated samples. For example if I see a consistent, large reduction in DNA methylation in a certain gene that suggests that there is more gene expression at that gene (low methylation = expression, high methylation = no expression). I can actually overlay this with my RNA sequencing data to see if that gene does actually increase expression! It's pretty cool. I mean you have to validate everything you see in your sequencing data with specific experiments but you can find some very interesting things. So what was the catch (besides learning how to make my computer do this stuff)? It takes time. It took me a full year to analyse my DNA methylation data and validate what I found. I have only started analysing my RNA-Seq data and I can tell you I have sat for 7 hours today watching my computer do aligning on my samples (it's only done 5 out of 9). And god forbid I put a comma in the wrong place or didn't add some arbitrary bit of syntax! I honestly spent a full day trying to figure out why the code I had written didn't work after the computer kept spitting out the "how to" file for the function I had used. I had done exactly what the were saying...except I didn't add two dashes, I had only added one. A bloody dash. My take home message is the more information we have the more we know. Seems simple right? The gathering of that data is in the whole pretty easy to be honest and a lot cheaper than it once was (though both of my sequencing experiments cost a total of around £9,000 - £10,000 each to get the data). The challenge is analysing that data. Handling terabytes of data to find even one gene shows a change in expression is a mammoth task. We need more people who can pick up a pipette and run an experiment as well as analyse the results of that experiment. If you are interested in learning any coding language there are lots of resources online as well as courses you can do. My supervisor (James Flanagan) and a fellow bioinformatician (he's a genius - Ed Curry) run a masters in Imperial in cancer informatics. It may seem daunting but if I can learn it so can you. And not just for cancer research or science in general. Knowing how to code could benefit a lot of industries. Bioinformatics! It's the future people! Sure how are you going to programme your robot in the future if you don't know code?? Resources I found useful: www.youtube.com/user/marinstatlectures www.tutorialspoint.com/r/ www.coursera.org/learn/data-scientists-tools www.imperial.ac.uk/study/pg/medicine/cancer-informatics/

Time done: 30 months

Time left in lab: 9 months Time to write up: 9 months Mood: wildly bouncing from euphoria to depression So I thought I would do a quick update on how my PhD is going since it’s been a while. I am officially ok with my hypothesis! Before Christmas was the hardest my whole PhD has been. I had spent a year analysing and testing my Illumina MethylationEPIC array (which looks at over 850,000 CpG sites across the genome - not that many considering how many there actually are). I found sites that had significant increases and decreases in methylation when I treat with my drug, spent months validating them using pyrosequencing and what did I find? Nothing. It didn’t validate. It was soul crushing. Buuuut I bounced back. Had a massive rethink with James (my supervisor). We thought about what my drug theoretically does and how that could affect epigenetics and I came up with a new, testable hypothesis. We were assuming my drug does a very specific thing that can be reproduced over and over (eg it always causes the same change in DNA methylation in the same place regardless of what cell line I use or how many times I test it). But maybe it’s not so specific but a bit more random, which is totally fine! This new direction also means my Illumina MethylationEPIC array analysis wasn’t a waste of time. Celebrations all around! And it seems to be going well so far. Well except that I have been troubleshooting the same western blot for nearly three months (and beating my head against a wall. Chairs may have nearly been flung through windows). There has been some tears not gonna lie. It’s hard to do the same 2-4 day experiment over and over to prove the result you got in the first place (in bloody January) was correct all along. Science - when you know you’re right but you have to show all the wrong ways to do it to prove you’re right! So what’s the plan now? Well I am going to the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Conference 2018 Chicago in April (there will be many vlogs, blogs etc) to present what I’ve found so far! Absolutely terrifying since I’ve only started to believe in my results like....last week. I have about 9 months left of work in the lab before I need to write it all as a thesis. That will consist of learning a few new techniques (RNA-seq, ChIP-PCR) and to get a bit more of an idea of what’s going on and how I can sum this all up in a pretty bow. I’m also getting another masters student to supervise (YAY) which I’m very excited about because I really like the project I wrote and the results regardless of what comes out are gonna be very interesting. She’s starting at the start of May and finishing up in September. I need to write some papers! I apparently have to publish my data (who knew) so the next six months will be writing up what I've done so far in a paper, getting it peer reviewed by people in my group so I can find any holes and plug them before December. I can then sent the actual papers off for real peer review and (hopefully) publication. And that's it. Sounds simple enough but it's taken 7.30am starts working 5-7 days a week to sum up everything I've done since August in a few paragraphs. I've even started drinking coffee in work. I shake violently when I drink coffee. It's not a good idea. I have one last thing to say to anyone thinking of doing a PhD, to people currently doing PhDs or anyone living with a person doing a PhD: To the person thinking of doing a PhD: be prepared. I want to scream at you "DON'T DO IT, IT'LL RUIN YOUR LIFE" but I won't. We need more researchers so we need more PhDs. But I will say be prepared. It is not all rainbows and unicorns. It's hard and it will drain the soul out of you. But then you'll get a result and feel like the smartest person in the world. You will love and hate the 3-4 years of your life doing a PhD. But really...be prepared to hate it a lot more of that time than you think. To the person currently doing their PhD: you are a god damn hero. Keep going. You may feel like you're drowning or that "maybe a masters for this isn't so bad, I should give up". DON'T. You have given your blood, sweat and tears to this thing. You are going to finish. Even if I have to carry you. But seriously. You have got this. You are smarter than you know, you are incredibly dedicated and you will finish. No one knows what doing a PhD feels like until they have done one. No ones knows the soul crushing pain. I know. And I know you have got this. To the person living with a PhD: please be patient. I know you don't understand what they're doing. I know you don't get why a little comma could cause a massive mental breakdown, the consumption of ALL of the ice cream and you getting shouted at but trust me there's a reason. It's hours, weeks, months or years worth of work that your loved one has just watched go down the drain (this specific example is for programmers but is applicable to all types of PhD). Just keep supporting and loving and caring for the lunatic PhD because they need it. And thank you for being there. Your presence means more than you will ever know. PS: I know I haven't been posting a lot. I do apologise but every second of my waking life is going into completing my AACR poster so bear with me.

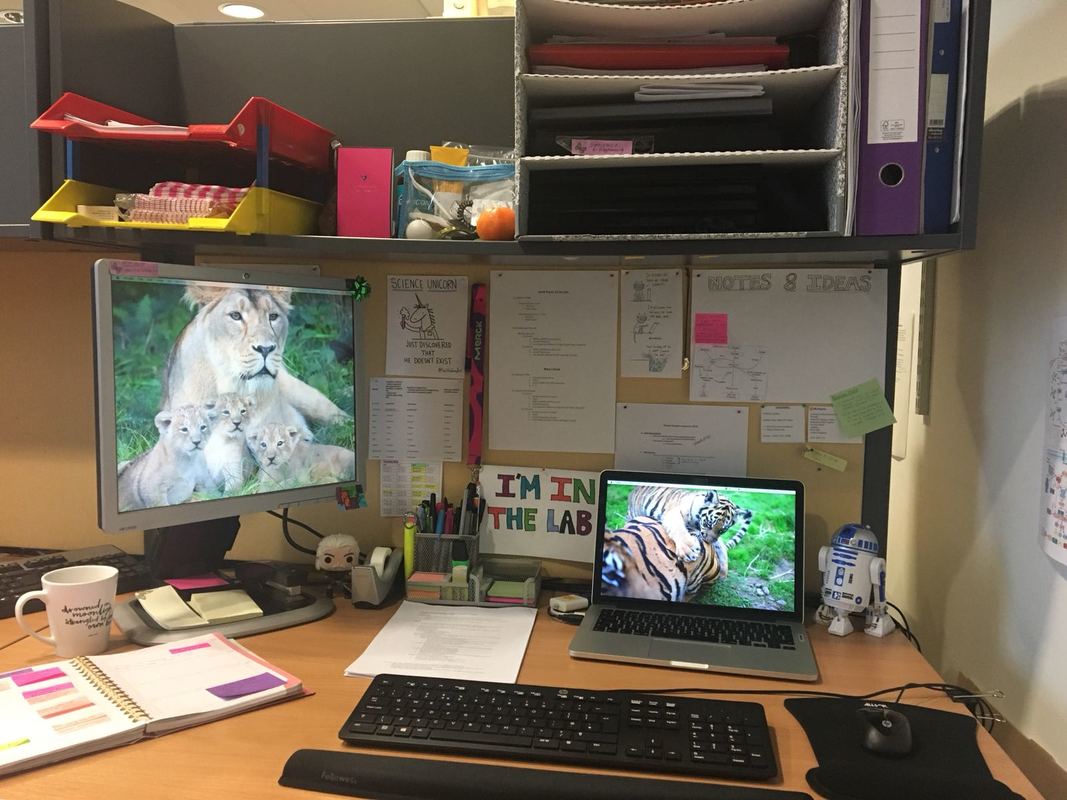

PPS: Apparently I have a very neat desk in my office and all other desks should aspire to look like mine......Weird email sent around the office!? So.....don't get too jealous everyone...

Cute animal photos keeping me sane are courtesy of the wonderful Fota Wildlife Park Ranger (Liam) supporting this lunatic PhD (me).

You may (or may not) have noticed that my blog has been all but quiet and desolate the last three months. This is completely my fault and an unconscious act of neglect. There are two main reasons why I have been so absent and hopefully I can give you many excuses to explain these reasons while also updating you on my progress.

The first reason is work. In mid-August I had what's known here as a Late Stage Review (LSR). This is something all Imperial PhD students are required to do in order to complete their PhD. The aim is to present your results and future plans after around 2 years of doing your PhD. You make up a report and do a presentation for two examiners. They judge your work and your ability to complete your PhD and sign you off. Usually they don't fail people (there is always the possibility) and the idea is for them to give you ideas for finishing your thesis and focusing your work. Obviously you want to present as much good data as possible. Hence the absence beforehand. I spent all my time writing the report and generating as much data as I could. All in all the LSR went fine. My work is satisfactory enough to continue. However I am not going to lie I was disappointed afterwards. I thought going in that they would help me narrow down and focus on the more important aspects of my project but instead I was told to "expand more to focus more". I realistically have 12 months left in the lab. This was not what I wanted to hear. I need to add more work to quite frankly an already daunting amount of work. Following from that I wanted to finish up at least one part of my project (validating my significant probes found from the DNA methylation array in another format i.e pyrosequencing). And this you will be happy to know showed...........nothing. Bupkis. Nada. I have negative results. While this is not an epic failure (as my brain wants me to believe) nor is it a triumph. Essentially what this means is I need to go back to my plan and look at the question a different way. And this is when I appreciated the LSR. Yes I needed to do more work but actually it gave me an opportunity to approach my project at a slightly different angle and who knows maybe something will work. I am now in the stages of planning and implementing that work. And who knows maybe in a few months time I will have something positive to talk about. The other reason I have been absent is I went on a 17 day holiday. I travelled to Rome, Sicily, Dublin and Cork. It was amazing and relaxing. And I didn't have to worry about my project or stress about what I needed to do next. I even slept the whole way through a night for the first time in, well, years. It was incredible and for anyone looking for their next holiday destination I highly recommend Sicily. Get a car like we did, drive around and soak it all in. Mountains, crystal clear water, food. A must really. And finally on a slightly different note I am taking up some teaching! An ex-member of our lab, Kirsty, is part of a team which has created a brand new innovative BSc undergraduate programme in Imperial. The course focuses on interactive learning and face-to-face teaching. It will be one of the first courses of its kind and hopefully not the last. Part of this course is to teach laboratory skills, called lab pods. I will basically be a part of a team of PhD students in these lab pods who will help guide students through techniques like cell culture and western blotting. Guide being the operative word. Unlike traditional teaching labs where I would show them what to do and answer all of their questions for them, this lab aims to make scientists. So I am really there to watch and provide last resort help. The idea is that the students will get a protocol, read through it and do the experiment. If it goes wrong then they have to figure out why. Exactly like anyone working in a lab would. Besides having a master student, I haven't really taught before so this is a new and exciting experience! Terrifying (especially when you realise you're about 10 years older than they are) but exciting. And that's what I've been doing. hopefully I will be a bit more dedicated to the blog and I can keep you updated on my work, my teaching experience and also complete a few posts (such as my "What the Hell? - Cancer" series). Btw I am not quitting this PhD any time soon in case you were worried.

In today's blog post I am going to talk about something very personal. I am going to talk to you about what research can do to you physically and why you need to protect yourself.

The physical price I have had to pay has not been a pleasant one. Ignoring the constant exhaustion because you're stress dreaming every other night about a decimal place, I have recently been diagnosed with repetitive strain injury (RSI) in my right wrist. For those that don't know me, my dominant hand is my right. This makes basic every day things like washing my hair and dressing a constant struggle. You can imagine how well I can pipette or type. What is RSI? Repetitive strain injury (RSI) is an umbrella term for injury caused to tendons or muscles that experience constant use. There are many types of RSI including carpal tunnel syndrome and tendonitis. In fact I have tendonitis and tenosynovitis (i.e inflammation of two tendons in my wrist and thumb and inflammation of the muscle sheath that covers them). The pain can reach all the way up into my elbow and shoulder. I also have a good deal of muscle weakness in my right wrist, thumb and fingers. For more information about RSI: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Repetitive-strain-injury/Pages/Diagnosis.aspx What Happened? I started developing pain in my hand in September 2016 but, as I do, I ignored it. It wasn't until I had an extremely important, sensitive experiment to do in November 2016 did my hand pain become a massive problem. I was unable to fully stretch my fingers or make a full fist. I had an almost claw hand. My knuckles were sore and I had pins and needles in my index finger (almost like it wasn't my own). Bending my wrist in any direction was agony. This, as you can imagine, made using pipettes incredibly difficult. Thankfully I work with some extraordinary people. The lab manager here, Nahal, also suffers with RSI and recognised the signs immediately. She pushed me to seek help and to stop working. She even helped me with the final stages of my big experiment (I had been building up to it for a year). I got to use a fully automated single arm machine which plated up my experiments for me. It was amazing! With Nahal's help, along with others in my lab (Annelie, Francesca, Ayse and Ebtihal), I managed to finish my experiment with pretty decent results. Once I was done in the lab, I got help from the impeccable staff of the Occupational Health (OH) here in Imperial College London. They did assessments and in cooperation with my GP I had x-rays and blood tests. OH also provided physiotherapy to start me on the road to recovery. Thankfully I had a month at Christmas to rest my hand and (as you know) three weeks in France doing computer analysis to further rest my hand. I did go back to work after I came back from France, however I greatly reduced my lab hours to 1-2 hours per day, ONLY 5 days a week. What Caused my RSI? Working too hard. I mean working myself hard. For 9 months during the first year of my PhD I worked 7 days a week, up to 50-70 hours a week. 90% of this time was in a lab constantly doing experiments (sometimes up to 6 or 7 a day, all at the same time). I actually calculated that I worked more weekend days in a four month period than I had taken off from January to September (including a two week holiday in September and Easter). I am a bit mad, I'm not going to lie. It has been not-so-subtly suggested more than once that I should seek mental health care. I don't really self-preserve. I push myself a lot. I need to be perfect and when I'm not I punish myself for my failure. When I'm not in work, I drive myself mad thinking about work (remember I mentioned stress dreams). This constant need to push myself effects my sleep patterns, eating patterns and my ability to feel and ignore pain. I have low grade chronic lower back pain from a traffic accident in 2009 but anyone looking at me would never guess. I also have no ability to say "no". I have organised lab retreats, lab trips, charity events and raffles. I currently run the epigenetic unit meetings and manage (from a distance) the group journal club as well. As a CRUK funded researcher I have also said yes to (almost) everything CRUK have asked me to do. This means taking time off work to go to the PGA tour or half days to bucket collect etc. No matter what someone asks of me I will always say yes and give 1000%. And honestly, I love it. I love helping out, no matter what I'm asked to do. It gives me a sense of purpose, like I'm doing something right even if my lab work is going to hell. As I said I am a bit mad. But all of this has caught up to me and now my work and potentially my career is suffering for it. What is happening now (22/03/2017): It is not going well. While the break and medication did reduce my pain and help me feel like I was getting back to normal, I was in fact kidding myself. My wrist muscles are pretty weak. I keep dropping things, which as you can imagine in a lab can be dangerous, and the pain is almost as bad as it was in November. Currently I am doing physiotherapy with the NHS. I am in a splint which does not let me move my thumb at all and I am doing strengthening exercises (I've even set alarms to remind myself). I am no longer in the lab. I am only doing computer analysis and that is pretty damn slow itself. Writing and typing is like being stabbed with tiny needles. I no longer work weekends (even on the computer). I have even been reduced to just cardio in the gym (I exercise 5-6 times a week because it calms me and makes me happy) which is INCREDIBLY BORING! All in all I am recovering but slowly. The moral of the story? No matter what pressure you're under, no matter who puts that pressure on you, you need to protect yourself. My hand is my career. Without it I can no longer work in a lab. If I don't get over my own psychological issues and buck up I could be disabled for god only knows how long. This is WAY easier said than done. I am working on it. Part of the reason why I started this blog (you'll notice I started in November) is to alleviate some of the guilt I feel not working. For anyone who reads this who does lab or computer work PLEASE PLEASE PROTECT YOUR HANDS. I honestly mean it. I was you 6 months ago, not really paying attention to all those "ergonomic advice memos" and now I'm here, 6 months on struggling to wash my hair because my hand hurts so much. You do NOT want to be me! Thankfully I have become a bit of an example in my group and people are paying more attention to their working practice. I have brand new ergonomic pipettes (THANKS JAMES!!) and a new look on my working life. I will never have a relaxed attitude about working and being the best but I am definitely going to take my time from now on. I hope my hand does get better and I can get back some of my life 6 months ago (not all of it, weekends will have to become work free zones). I will keep you updated on how my recovery is going.

I wanted to write a quick post to acknowledge something I think is pretty great! I was recently (and by recently I mean this morning) included on the European Association for Cancer Research (EACR) fortnightly member's email bulletin!!! It's a big deal for me because it gives me hope that what I'm writing here isn't completely inept!

I want to say thank you to EACR for believing that my little blog is worth publicising and hopefully I can make them proud!

Bonjour de France!!

It's the New Year and a very sparkly new me (read: old me in better clothes) has headed to Lyon, France! Why you ask? Well I will tell you, calm down. I am in Lyon to visit the world renowned International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). *pause for dramatic effect and exclaims of awe* I know, I know pretty sweet. I'm here for three weeks as part of a research exchange! This research exchange has been generously funded by the European Association for Cancer Research (EACR) and I am very grateful for this opportunity. My goal here is to improve my knowledge about epidemiology and biostatistics (don't worry I have no idea what they mean either) plus meet new and interesting people! IARC is a pretty special place because it is completely dedicated to the study of cancer. People from all disciplines in science come together to work on this one problem. For example I am working with the Nutritional Epidemiology Group. Nutrition and diet are really key in the development and progression cancer so understanding more about these areas will give us a better chance of preventing the disease. I am enjoying Lyon so far. To date I have badly ordered a pizza with no French, got stuck trying to get into an underground station, been in the worlds longest queue (probably) and been snowed on. I have a lovely airbnb (thank you Catherine) near the main part of the city and it's only a 30-40 minute walk from IARC. It's very cold at the moment (hence the snow) but it's a nice cold. It's crisp and refreshing compared to the damp cold you get in Ireland or the UK. The people here are very nice and very helpful! I've had a few moments of failing to communicate with a native but a very kind person has come to my aid (rather embarrassingly I didn't learn any French for this trip which I really should've done). This has also been accompanied with frantic texts to my friend JoAnn who thankfully has lived in Lyon before and takes pity on idiots! UPDATE 1: I attended an interesting seminar this week by Professor Pär Stattin on cancer registries and how to make the information more easily accessed and used. Cancer registries are really important for epidemiologists and cancer researchers. These registries are made up of all the information your hospital/clinic would take when you are first referred. The registry gives you information on patient age, cancer type, first diagnosis, duration of treatment, recurrence etc. This information analyzed together can tell you how widespread certain cancers are across countries and continents. For example cancer registries help determine the most common cancers (in the UK and US Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer). This information can also be used to determine survival and mortality. UPDATE 2: SIGHTSEEING! My first weekend in Lyon (1 of 2) was lovely. I tried to do a bit of sightseeing but it was however FREEZING (it's currently -1 and boy can you feel it). On Saturday I wandered the streets of the Vieux-Lyon (the old city) and visited the musées Gadagne to learn about Lyon's history. There is the option to visit a puppet museum there but they freak me out so I passed. It's weird sightseeing on your own, I don't know if anyone has tried it. I'd love to hear how you do it 'cause I struggled a bit. Not the being alone certainly but the "pity face" that everyone gives you because obviously you're unloved. I digress. Lyon is beautiful and full of gorgeous historic buildings. On Sunday I walked to the parc de la Tête d'Or, which has a small zoo and botanical gardens. I strolled (read: power walked) down the river bank, passing a farmers market and wandered around for a few hours in the snowy park. I hope to see more on my second (read: final) weekend in Lyon.

Some pictures from my first weekend to see more visit the Gallery.

UPDATE 3:

53rd Scientific Council 2017: The Scientific Council meets annually to discuss key issues in cancer research. Representatives from cancer agencies from different countries across the world (including Qatar, Ireland, UK, Brazil and Canada) come to assess short, medium and long-term strategies in tackling cancer worldwide. IARC hosted this council while I was here and I had the opportunity to watch (online) some of the meeting and see some policy changes made. It was very interesting and a great insight into the important work IARC does. UPDATE 4: I have now completed my three-week research exchange in IARC. It was a really rewarding experience both professionally and personally. I learnt a lot about data analysis and the work that goes into being as accurate as you can while still providing interpretable statistical models. I met a lot of great people while in Lyon and benefitted greatly from the buddy system implemented by IARC ‘s Early Career Scientist Association (ECSA). I would like to say a huge thank you to my supervisor Dr. Marc Gunter for allowing me to come. I would also like to thank Dr. Pietro Ferrari’s group (Flavie and Nada) for helping with my data analysis and for making a statistical model to test my data on. Mostly I want to thank Rachel, Maria, Tom and Vibha and all the Nutritional Epidemiology Group for making me feel so welcome.  Photo Credit: International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://www.iarc.fr/en/ Photo Credit: International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://www.iarc.fr/en/

IARC was formed in 1965 by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an independent cancer research facility. IARC has a Governing Counsel made up of 25 countries across the globe, allowing IARC to make vital decisions about cancer research without pressures from external sources. More Informaion: https://www.iarc.fr/en/

|

AuthorMy name is Caitriona and I am a PhD student at Imperial College London, UK. Categories

All

|